Business Week: Is housing set to blow?

Buyer (And Seller) Beware

Is housing set to blow, or are there more gains ahead? Here's how to navigate an anxious market

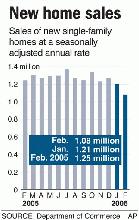

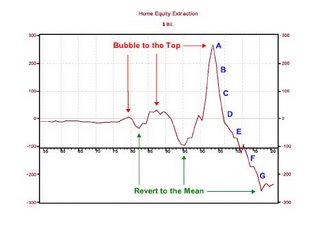

Confused about the direction of the housing market? It's no wonder. You hear stories about sellers slashing listing prices to attract buyers, but home prices nationally have risen more than 10% over the past year. Inventories of unsold homes are on the rise, yet homebuilder Lennar Corp. just reported a 34% jump in earnings. And the much feared rise in 30-year mortgage rates seems to have stalled. Advertisement

In this muddled situation, what should you do, whether you're on the buyer's end of the seesaw or the seller's? Cut your price now or hold out for more? Rent or buy? Go for a bigger house or a smaller one? In the New York City suburb of Larchmont, N.Y., where prices are off their peaks, confusion reigns. Says Realtor Carol Higgins: "Buyers are complaining that prices are astronomical, but sellers are still thinking they'll get what they saw their neighbors get last year."

See 2005 Bay Area Stats

Let's be honest: No one can predict with certainty which way home prices will go in the next year or so. Over the past several years almost everyone who has tried to forecast the direction of the housing market has been wrong (though BusinessWeek Chief Economist Michael Mandel takes a shot).

We can, however, tell you how to avoid some critical psychological and financial mistakes in today's anxious markets. No matter how smart you are, it's easy to fall into certain mental traps that can cost big bucks. Instead of concentrating on the fundamentals, people tend to be ruled by their feelings and the compulsion to compare themselves with their neighbors. If your brother-in-law made a killing in real estate, you're determined to do the same. "So much of what drives the housing market is human interpersonal dynamics," says Yale University economist Robert J. Shiller.

What follows is a set of practical guidelines for navigating today's choppy and uncertain real estate markets. The suggestions come from behavioral economists, who study the kinds of erroneous decisions people tend to make repeatedly, as well as from hands-on real estate experts. In addition we'll tell you which cities are more vulnerable to a drop in prices and which are less at risk.

CONTRARIAN COOL

A first rule of thumb is to avoid herd behavior, which is what lured a lot of people into overpriced houses in the first place. The expectation of rising prices became a self-fulfilling prophecy as office mates and in-laws tried to leapfrog each other. The prevailing mindset: "You see people who aren't particularly talented, who aren't hard-working, who buy a house with nothing down, and they've been getting rich doing it. If they're getting richer, then you're falling behind," says Robert H. Frank, a Cornell University economist and author of Luxury Fever. Another attraction of herd behavior is safety in numbers. Millions of buyers can't all be wrong, can they?

Also, behavioral economists have discovered in laboratory experiments another attraction of herd behavior. Misery really does love company: People seem to worry less about losing a lot of money if they think everyone around them will suffer the same fate.

Still, the rewards of thinking independently can be high. Richard X. Bove put on his green eyeshade and concluded that Florida real estate was overpriced. So earlier this year he bailed out. Bove sold his 5,600-square-foot St. Petersburg (Fla.) home for $1.2 million, twice what he paid for it a decade ago. The plan was to rent while he waited out a housing decline. But Bove couldn't find a suitable rental, so he lowballed a four-bedroom house in Tampa and got it for $740,000 -- 30% below the asking price.

In a softening real estate market, one of the most dangerous mental mistakes is what behavioral economists call "loss aversion," which is the tendency to do dumb things to avoid, at all costs, recording a loss. Some sellers are so averse, they gamble the market will bounce back rather than cut their prices.

Indeed, real estate agents often have a much clearer idea than sellers that demand has softened. "The hardest thing is to convince the sellers of the change in the market," says Alfonsina Rechichi "There's a sense of fear among brokers that you sense at open houses," says Saul Greenstein, a renter, who suspended his house search because prices were too high. "The self-confidence you saw a year ago has been replaced by fear and pandering."

Even owners who stand to make a big profit on a sale often set the price too high. In this case the mental error isn't loss aversion but outdated thinking. New research shows that sellers set their listing price, in part, based on information six months to nine months old. That means if you don't pay close attention, you will tend to underprice in a rising market and overprice in a falling one.

STUNG ON BOTH ENDS

Two smart people who just might be guilty of that in the New York City suburbs are Joe Watson, a neurosurgeon, and his wife, JoAnn, who has a PhD in genetics. In relocating from New Rochelle, N.Y., to McLean, Va., they planned to come out even by selling and buying at roughly the same price: $1.2 million. Now they're getting stung on both ends of the transaction. The Virginia house is costing them "significantly more" than $1.2 million, and they can't get what they want for their 1937 Tudor in New Rochelle. Says JoAnn: "We were advised by two brokers to price it initially at $999,999, but my husband and I wanted to start at $1.19 million because we thought we could get it." Even after nudging the price down to $1.09 million, though, there haven't been any offers. JoAnn has taken to blaming the shoppers. "It's a great house," she complains. "Why doesn't anyone realize it?"

The gravest danger of dragging your heels on price cuts in a sinking market is that you can "follow the market down," never managing to sell because your price is always just a little too high, says Christopher J. Mayer, a Columbia Business School economist. He and David Genesove of Hebrew University in Jerusalem found that when prices were falling in Boston in the early 1990s, two-thirds of the houses that came on the market were eventually withdrawn without a sale.

In parts of the country where the market is still strong, a common sin continues to be overconfidence. Owners typically don't seriously consider a wide enough range of potential housing market outcomes, including the possibility of a steep decline. That leads people to take more risks than they should.

Nordstrom Inc. managers Robert J. Gelb, 50, and his wife Cindy, 47, of Mercer Island, Wash., own the house they live in as well as two they bought for their children. Gelb says last year's appreciation on the house his son occupies was greater than his son's salary at Nordstrom's. For the house they bought for their college-student daughter, they put down 3% and got a negative-amortization loan, which Gelb says makes it a better deal than renting her a dorm room. "Worst case is that I sell it for what I paid for it," he says. His take on housing is nonchalant: "Even if it is a bubble...it would be a slow leak. Maybe some people would say I'm naive, but I don't see a downside."

Optimist Gelb is well-off enough to take a slump in stride. Still, he might want to have a conversation with Linda R. Fink, 57, who manages a city park with a bicycle-racing track in Indianapolis. She knows all about slow leaks. Fink bought a house in November, 2000, for $120,000. At the time, Fink says, she viewed the purchase as an investment and reassured herself that "if something happens five or six years down the road, I'll be O.K. I can sell it and get out."

Instead, Fink watched home prices in her neighborhood fall and fall. She bailed out in 2004 for $92,000 in a "short sale," meaning the lender got the proceeds of the sale but not all it was owed. Says Fink: "It all just blew up on me."

Rent-vs.-buy decisions are a perfect example of what the housing market can learn from behavioral economics. If financial efficiency were all that mattered, more people would be renting nice houses instead of buying them, even taking into account the home mortgage-interest deduction. But there's something comforting about owning the place where you lay your head on the pillow each night. "It's worked out so phenomenal," exults first-time buyer Obrey M. Minor, a 27-year-old special education teacher who bought his first house last year with his wife in the Houston suburb of Katy.

You can hear how much homeownership matters by talking to people like Annapolis (Md.) renter April McKinley, a health-care consultant who recently moved with her police officer husband from Pittsburgh to the Washington (D.C.) area and ran smack into a wall of high prices. "Here I am, a productive citizen, and I can't afford to own a piece of it," says McKinley.

Especially in upscale communities, social pressure to buy is intense. Jonathan Miller, recalls that when he and his family moved to upper-crust Darien, Conn., 15 years ago and rented for a year, "we were absolutely second-class citizens. It was very unpleasant."

Call it "castle thinking" -- the notion that a home is a fortress against a cruel world (table). And it's perfectly defensible. But in many markets the total monthly costs of renting are far below the total monthly costs of owning the same property -- 62% cheaper in San Diego, for example, according to Torto Wheaton Research. So you owe it to yourself to be aware that your castle thinking can be a costly predilection.

Neuroscientists have even discovered the place in your brain that makes you spend too much on a house. Far from behaving perfectly rationally, real people are pushed and pulled by signals emanating from below the neocortex -- the primitive "lizard brain." That may be why there are so many homes with empty marble foyers, faux Roman columns, dust-collecting Jacuzzis, and exotic drooping conifers on the lawn.

MANAGE YOUR CRAVINGS

What people can do is be aware of their human tendency toward status-seeking. Cornell's Frank suggests channeling the drive more productively. If getting your kids into a good school district is a priority, for example, try to satisfy your lust for status by buying a smallish house in a prime school district instead of a showplace in a worse one. "You have some choice," says Frank. "There's room to do better."

A foible that helps account for America's obsession with real estate is what you might call the tangibility fallacy. It's the all-too-human tendency to regard tangible things like houses as more stable and trustworthy than intangible ones like stocks and bonds. It's true that a house provides more comfort than a book entry in a stockbroking account. But that doesn't mean it's a better investment.

In fact, except for the past few years, house prices have risen only 1% or so faster than the rate of inflation. But just try telling that to Ron DeLucia of Jacksonville, Fla., who at the age of 68 is selling his current home and buying a bigger one across town, in part because he and his wife think a house is a more trustworthy asset than shares of stock. Says DeLucia: "We all went through the crash of the market. I lost $150,000. You never get that money back. I think the stock market is going to go down. I'd rather put the money we have in hard assets like property."

And finally, it's easy to lose your head over housing if your thinking isn't disciplined. To find your moorings, try to focus on the fundamental factors that determine value. On that score it's somewhat reassuring to realize that prices in the U.S., though high, are not out of line with other major countries. Finding properties that are exactly comparable is difficult. But in an unscientific survey, BusinessWeek correspondents rounded up listings for a few homes for sale around the world. There's a four-bedroom in Kleinmachnow, a pricey suburb of Berlin, going for $525,000. In the upscale Golders Green neighborhood of London, 20 minutes from the city center, a four-bedroom house is on the market for $1.56 million. And in Tokyo's Suginami Ward, three bedrooms squeezed into a cozy 987 square feet go for $566,000. These kinds of prices have a familiar ring.

READING THE TEA LEAVES

Within the U.S., however, prices in some housing markets do raise red flags. A good starting point is to look at the affordability of homes for ordinary families. By that measure greater Los Angeles was the worst in the nation in the fourth quarter of 2005. Only 2% of homes sold there were affordable by families earning the area's median income, according to the National Association of Home Builders. New York wasn't much better at 6%. Other expensive big cities included San Francisco at 7%, Miami at 14%, Boston at 24%, and Washington, D.C., at 27%. Tops in affordability among big cities were places like Dallas, with 60% of homes sold affordable by median-income families, San Antonio and Houston at 57%, and Chicago at 48%.

Of course, unaffordability is a chronic condition in cities like New York, so it's not necessarily evidence that a sharp correction is in the offing. Economists at Global Insight Inc. and National City Corp. deal with that by looking at whether metro areas have departed from their own historical trends in affordability. They conclude that in the fourth quarter, 42% of the top 299 metro markets were "extremely overvalued and at risk for a price correction." Florida and California dominate this historically adjusted list. Boston and New York look more reasonable by this measure, and San Francisco appears a bit less bubbly. Texas still comes out looking cheap.

Yet another way to identify a problem area is to compare rents to sales prices. The idea here is that if people's monthly payments to own a house are much higher than what they would spend to rent the same place, tax considerations included, then they must be banking on prices going up so they can sell for a profit someday. That leaves them exposed if prices don't rise. By this measure, San Diego is one of the frothiest areas of the country. But Tampa, Orlando, and New York, which come out as expensive by some other measures, aren't so costly by this one.

This year millions of American households will buy a home. The process will always be lengthy and a big deal. But whether you are a buyer or seller, you don't have to feel quite so lost.